Some get dealt simple hands

Some walk the common paths, all nice and worn

But all folks are damaged goods

It ain't a talk of "if," just one of "when" and "how"

So, collect your scars and wear 'em well

Your blood's as good an ink as any

Some walk the common paths, all nice and worn

But all folks are damaged goods

It ain't a talk of "if," just one of "when" and "how"

So, collect your scars and wear 'em well

Your blood's as good an ink as any

Late January, 1779 — New York City

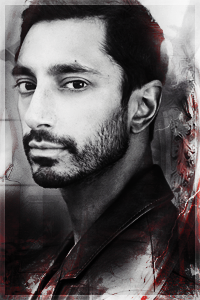

The irony fit all too well, he would think later (years later), when he had finally worked his way fully out of that murky stretch of being - slave to a hunger so strong it was almost blinding - long enough to think.

Died on holy ground.

Or didn't die, rather. That depended, probably, on one's interpretation of dying.

This was it, anyway, New York's Holy Ground. Holy Ground, it had been baptised years ago; he'd appreciated it as a bit of entertaining wit, even then, hearing the tale for himself. A district that stretched from King's College to the hallowed ground of Trinity Church, not just bordering on the godly (not his god, of course, but that had never been his quibble) but nestled in its very bosom, owned by it. Some negligent landlord the Church made, turning the other cheek to all sorts, as long as the working girls pranced into the pews every Sunday in their best rags. The fire after Washington and his men had fled the city had swept through and stamped out some of the worst of it, the whorehouses and taverns and dank soldiers' encampments, the gambling and fights, the lawlessness, the din. But what could fire do, really, scorching the earth as though the vermin wouldn't come right back, scuttling out of the debris like cockroaches, springing up again like weeds, unheeded?

It looked more of a skeleton now, burnt-out buildings and blackened panes still scattered as proof amongst the rebuilt slums. And still, worse than he could ever have imagined, more than any of these muggles could: unhallowed ground, home to the most unhallowed things.

"Coming, Zahir?"

Ismail - Ishmael, as they all knew him here - glanced over his shoulder and shook his head. "Nah," he said lightly, all broad grin and nonchalant shrug, like he spent time out here alone every day. In all honesty, it wasn't that much worse than Liverpool. "I'll catch you up."

"You know where to find me," the soldier - a Queen's Ranger, none of those redcoats supposed to be this far out of their barracks by now (though as if any of them could follow an order if it beat them in the face) - called back, as he shouldered his musket and trudged off back the way they'd come. Ishmael sure did, and he'd bet all the money he had on it: that bastard would be trouserless in his girl's tent until the last second he had, 'til they were all rounded up back by the docks and set to be ferried across the river to their next foray. Since he was crew on that sloop, Ishmael's activities ran to the same deadline; unlike his soldier friend, he was spending his time a little more creatively.

Earning rather than spending, actually. Coin changed hands easily here (best keep away from bills, what with the way no one knew which way the war would go, couldn't say whether Continental dollars would ever be more than wasted paper, or if British pound notes might as well get flushed out to sea), and Ismail Zahir might not be a scholar or a gentleman, mightn't have an education or a pedigree or even a blasted uniform - but he did have his wits about him and a damned good eye for opportunity. More was the pity he hadn't gotten to Hogwarts after all - hadn't gotten hold of a wand for long enough to learn how to use it - else magic might have been an extra weight on the balance, a little sleight of hand and a spare trick up his sleeve. He had decent luck anyway, usually, whether it was in betting right on a fight, knowing when to take a risk, or how best to talk his way out of a scrape.

Not that he was a criminal or a common thief, mind. Trade was a perfectly honest business... a perfectly fair business, now. He got what he wanted, and so did his partners. Privateering was all well and good - when his ship had first been decommissioned he'd joined another British privateering brig, requisitioning from the rebels - but the profits were shared and parceled up, and Ishmael had found he could do better on his own. It helped, he thought, that he wasn't in the war for the principle of it; after all, the patriots were in as much need of black market stores as the British troops occupying the city.

Ishmael whistled as he wandered slowly towards the meeting place - goodbye, fare ye well, his unthinking tune was, a shanty he'd known since he'd started working as a boy, we're homeward bound to Liverpool town - oblivious to the dark as it drew further in, the shadows growing longer through the murky, muddied January streets. He scratched idly at his neck (his neckerchief already so sloppily loosened under his coat that it wasn't in the way) and regretted now not wearing a cap in this chill. The cold was the worst of his problems, he'd thought. He'd have been more worried about hiding his identity if anyone here cared about dodgy things happening right under their nose.

He'd have been more worried, he supposed, if there was anyone here to begin with.

He probably should have grown worried a lot faster than he did, looking back. But, all the same, looking back - he was so young. A week or two off twenty-three, and about as foolish as anyone would expect. He'd not been fazed by much, back then; he had always been good at taking things in stride.

Perhaps this was why he was so slow to react when he stumbled across the body. It had been partially hidden from view, slumped face down behind a stack of barrels outside, but he'd almost stumbled over a foot, and then he'd seen the hand, bloodless and white, stretched out past the barrels into the street.

And perhaps the surprise of seeing the body was why he didn't hear the faintest stir of movement.

post count: 1000 words

Died on holy ground.

Or didn't die, rather. That depended, probably, on one's interpretation of dying.

This was it, anyway, New York's Holy Ground. Holy Ground, it had been baptised years ago; he'd appreciated it as a bit of entertaining wit, even then, hearing the tale for himself. A district that stretched from King's College to the hallowed ground of Trinity Church, not just bordering on the godly (not his god, of course, but that had never been his quibble) but nestled in its very bosom, owned by it. Some negligent landlord the Church made, turning the other cheek to all sorts, as long as the working girls pranced into the pews every Sunday in their best rags. The fire after Washington and his men had fled the city had swept through and stamped out some of the worst of it, the whorehouses and taverns and dank soldiers' encampments, the gambling and fights, the lawlessness, the din. But what could fire do, really, scorching the earth as though the vermin wouldn't come right back, scuttling out of the debris like cockroaches, springing up again like weeds, unheeded?

It looked more of a skeleton now, burnt-out buildings and blackened panes still scattered as proof amongst the rebuilt slums. And still, worse than he could ever have imagined, more than any of these muggles could: unhallowed ground, home to the most unhallowed things.

"Coming, Zahir?"

Ismail - Ishmael, as they all knew him here - glanced over his shoulder and shook his head. "Nah," he said lightly, all broad grin and nonchalant shrug, like he spent time out here alone every day. In all honesty, it wasn't that much worse than Liverpool. "I'll catch you up."

"You know where to find me," the soldier - a Queen's Ranger, none of those redcoats supposed to be this far out of their barracks by now (though as if any of them could follow an order if it beat them in the face) - called back, as he shouldered his musket and trudged off back the way they'd come. Ishmael sure did, and he'd bet all the money he had on it: that bastard would be trouserless in his girl's tent until the last second he had, 'til they were all rounded up back by the docks and set to be ferried across the river to their next foray. Since he was crew on that sloop, Ishmael's activities ran to the same deadline; unlike his soldier friend, he was spending his time a little more creatively.

Earning rather than spending, actually. Coin changed hands easily here (best keep away from bills, what with the way no one knew which way the war would go, couldn't say whether Continental dollars would ever be more than wasted paper, or if British pound notes might as well get flushed out to sea), and Ismail Zahir might not be a scholar or a gentleman, mightn't have an education or a pedigree or even a blasted uniform - but he did have his wits about him and a damned good eye for opportunity. More was the pity he hadn't gotten to Hogwarts after all - hadn't gotten hold of a wand for long enough to learn how to use it - else magic might have been an extra weight on the balance, a little sleight of hand and a spare trick up his sleeve. He had decent luck anyway, usually, whether it was in betting right on a fight, knowing when to take a risk, or how best to talk his way out of a scrape.

Not that he was a criminal or a common thief, mind. Trade was a perfectly honest business... a perfectly fair business, now. He got what he wanted, and so did his partners. Privateering was all well and good - when his ship had first been decommissioned he'd joined another British privateering brig, requisitioning from the rebels - but the profits were shared and parceled up, and Ishmael had found he could do better on his own. It helped, he thought, that he wasn't in the war for the principle of it; after all, the patriots were in as much need of black market stores as the British troops occupying the city.

Ishmael whistled as he wandered slowly towards the meeting place - goodbye, fare ye well, his unthinking tune was, a shanty he'd known since he'd started working as a boy, we're homeward bound to Liverpool town - oblivious to the dark as it drew further in, the shadows growing longer through the murky, muddied January streets. He scratched idly at his neck (his neckerchief already so sloppily loosened under his coat that it wasn't in the way) and regretted now not wearing a cap in this chill. The cold was the worst of his problems, he'd thought. He'd have been more worried about hiding his identity if anyone here cared about dodgy things happening right under their nose.

He'd have been more worried, he supposed, if there was anyone here to begin with.

He probably should have grown worried a lot faster than he did, looking back. But, all the same, looking back - he was so young. A week or two off twenty-three, and about as foolish as anyone would expect. He'd not been fazed by much, back then; he had always been good at taking things in stride.

Perhaps this was why he was so slow to react when he stumbled across the body. It had been partially hidden from view, slumped face down behind a stack of barrels outside, but he'd almost stumbled over a foot, and then he'd seen the hand, bloodless and white, stretched out past the barrels into the street.

And perhaps the surprise of seeing the body was why he didn't hear the faintest stir of movement.

![[Image: xKclfq.png]](https://cdnw.nickpic.host/xKclfq.png)