She seemed in a good mood; relaxed; a gleam of laughter in her face and on her lips. Well, good. That meant the Forest hadn't been burned down by a mob or Hogsmeade massacred in his absence, at least (what he would be able to do about either event, he didn't know, but for the last few years he had always felt a sense of that precariousness circling their chosen home, like - ridiculously - everything would fall apart as soon as he left). This visit might actually be entertaining, then.

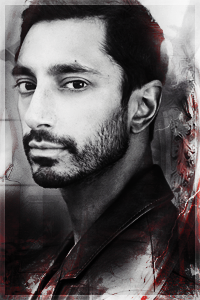

Galina was not that much older than him - in looks, perhaps, she was even a touch younger - but Ishmael had always been impressed by her somehow, as if there was some sort of knowing air about her, a natural authoritativeness to her stance, a certain poise and sagacity. He pretended that kind of thing sometimes - that he had once been some important, wealthy aristocrat of some foreign country, a rich young man with the world as his oyster - but however zealously he feigned those stories, Galina had always seemed a little too perceptive. Not that they had spoken too plainly about the past, ever, but Ishmael didn't get the feeling she believed any of the bullshit he spouted sometimes. She didn't call him out on it, sure, but perhaps it was because she had been that sort of person once, raised that way long ago; real enough that she could perceive a pretender.

Much as he respected her, Ishmael wasn't quite so certain he agreed with her assessment of cities, of the world. She took off her cloak, skin luminously pale even in the dim light of the abandoned house, and he grinned at her, leading the way through the first doorway into the sparsely furnished "sitting room", like Monty Morales and his other cronies ever invited in company of their own. He gestured freely at her to make herself welcome, fairly out of habit of hosting company himself, but once he had done so he shrugged at her, not entirely convinced.

"Oh, I don't know," Ishmael returned, never afraid to stir debate. "The skeleton might always be the same, but I don't know that that's what matters." A city was a city was a city, yes - each had its centre, its wealth and its poverty, its markets, its patterns and currents and throngs - but Ishmael had never felt particularly the same in any of them. London now was not Liverpool last century, nor was it wartorn New York, or bloody Paris, Rome or Athens or Porto or Istanbul, a far cry too from Karachi or Bombay or Calcutta. There were similarities to bind them all, but Ishmael's memories, even as an outsider, were all coloured in different shades, collected under different boughs. The skeleton was what classed the human, indeed, and they were all alike beneath: but it was not the skeleton, by anyone's account, that made someone who they were.

"I find nowhere's ever quite the same as the last," Ishmael explained, with a sly smile. "But the difference, see, is in the details. Maybe you've always been too brisk to notice, Galina," he said, not afraid of a little good-natured ribbing, even if she did not agree. "Maybe you've only ever been visiting, and not really living." He let out a laugh - he was not so certain many would call what they did living - but still, there was a glimmer of seriousness under what he was trying to say, something that he well believed: if you trapped yourself too well in the guise of outsider, then you would always be outside, never truly invited in. It was what they were made to be, mysterious figures flitting in and out under cover of darkness - and Ishmael knew in his heart that even his staying, here, in London, could not last forever - but even the pretence of it was something worth striving for. Better to find oneself part of the fabric of the city, if one could.

"It helps when you get to know the faces properly," Ishmael added, with another cheerful grin. That was part of the living here, see, existing in the space in a more rounded way than in picking off strangers on street corners and fleeing the consequences. Anything was made more memorable by being acquainted with the people... And Ishmael? He would go so far as to say he had friends in this city, which was something he suspected not all vampires could say. (That said, he wasn't sure how Galina would take the thought of being chummy with humans. She might think it beneath her.

But perhaps he could convince her of the benefits of it tonight.)

Galina was not that much older than him - in looks, perhaps, she was even a touch younger - but Ishmael had always been impressed by her somehow, as if there was some sort of knowing air about her, a natural authoritativeness to her stance, a certain poise and sagacity. He pretended that kind of thing sometimes - that he had once been some important, wealthy aristocrat of some foreign country, a rich young man with the world as his oyster - but however zealously he feigned those stories, Galina had always seemed a little too perceptive. Not that they had spoken too plainly about the past, ever, but Ishmael didn't get the feeling she believed any of the bullshit he spouted sometimes. She didn't call him out on it, sure, but perhaps it was because she had been that sort of person once, raised that way long ago; real enough that she could perceive a pretender.

Much as he respected her, Ishmael wasn't quite so certain he agreed with her assessment of cities, of the world. She took off her cloak, skin luminously pale even in the dim light of the abandoned house, and he grinned at her, leading the way through the first doorway into the sparsely furnished "sitting room", like Monty Morales and his other cronies ever invited in company of their own. He gestured freely at her to make herself welcome, fairly out of habit of hosting company himself, but once he had done so he shrugged at her, not entirely convinced.

"Oh, I don't know," Ishmael returned, never afraid to stir debate. "The skeleton might always be the same, but I don't know that that's what matters." A city was a city was a city, yes - each had its centre, its wealth and its poverty, its markets, its patterns and currents and throngs - but Ishmael had never felt particularly the same in any of them. London now was not Liverpool last century, nor was it wartorn New York, or bloody Paris, Rome or Athens or Porto or Istanbul, a far cry too from Karachi or Bombay or Calcutta. There were similarities to bind them all, but Ishmael's memories, even as an outsider, were all coloured in different shades, collected under different boughs. The skeleton was what classed the human, indeed, and they were all alike beneath: but it was not the skeleton, by anyone's account, that made someone who they were.

"I find nowhere's ever quite the same as the last," Ishmael explained, with a sly smile. "But the difference, see, is in the details. Maybe you've always been too brisk to notice, Galina," he said, not afraid of a little good-natured ribbing, even if she did not agree. "Maybe you've only ever been visiting, and not really living." He let out a laugh - he was not so certain many would call what they did living - but still, there was a glimmer of seriousness under what he was trying to say, something that he well believed: if you trapped yourself too well in the guise of outsider, then you would always be outside, never truly invited in. It was what they were made to be, mysterious figures flitting in and out under cover of darkness - and Ishmael knew in his heart that even his staying, here, in London, could not last forever - but even the pretence of it was something worth striving for. Better to find oneself part of the fabric of the city, if one could.

"It helps when you get to know the faces properly," Ishmael added, with another cheerful grin. That was part of the living here, see, existing in the space in a more rounded way than in picking off strangers on street corners and fleeing the consequences. Anything was made more memorable by being acquainted with the people... And Ishmael? He would go so far as to say he had friends in this city, which was something he suspected not all vampires could say. (That said, he wasn't sure how Galina would take the thought of being chummy with humans. She might think it beneath her.

But perhaps he could convince her of the benefits of it tonight.)