13 December, 1892 — Hebrides, Scotland

Neither Juliana nor Mr. Ainsworth were particularly religious, but they had observed the requirements for the reading of the banns all the same. There was no reason not to, since they had already agreed to a long engagement — Juliana being conscious that a short one, without a courtship preceding, might lead people to suspect something about her that she didn't want anyone suspecting. Because neither of them had an official church — and because the magical community was not so location-bound to different parishes as their Muggle counterparts, anyway — their intention to marry had been published in the Notices section of the Daily Prophet instead of being read before a congregation. It first went out in October, when they had determined the date of the wedding would be January; again in November; again a week ago. The next notice to be printed would be the announcement that the wedding was completed and she was now Mrs. Timothy Ainsworth.

None of their notices had run alongside any ominous riddles about impending murders, which Juliana had decided to take as a positive omen. Not that she needed divination to reassure her. The engagement had been nothing if not smooth. She had met his parents and his sisters, all of whom were lovely to her and seemed agreeable in general. Mr. Ainsworth had been accommodating to her every request, not that she had many. She had no grand visions of her wedding; unlike some girls, she had not been dreaming about this from a young age. But even that seemed alright; her fiance seemed to understand that she had defined the purpose of her life without romance in mind, and did not expect her to love him. They talked frequently now that their relationship had changed, and she enjoyed their conversations and his company more generally. They were friends, and he did not demand more from her.

Since they'd begun posting the notices in the Prophet she had been on the receiving end of at least a dozen letters of congratulations — some superficial and sparse, from acquaintances that merely recognized her name and remembered her face and were polite enough to write — others lengthy and full of inquiries, from friends who knew her well enough to be surprised by this sudden development. Every notice brought a new batch of mail, but each month the wave was a little smaller than the previous month's, and they never contained the letter she was hoping for. Juliana hadn't admitted to herself that she was scanning each envelope for his handwriting, not at first — but after three months of small, steady disappointments she couldn't keep denying it. She wanted to know what he thought, even if it was nothing good. Was he angry? (Did he have any reason to be angry? They hadn't spoken since —) Maybe he never thought of her at all anymore. Maybe he hadn't even seen the notices in the paper, even though they'd been published three times in as many months. Maybe he didn't have the paper regularly delivered — that seemed plausibly like him, living up in Scotland detached from the rest of the world, avoiding — (was he avoiding the world, or just avoiding her? She didn't know which she would have preferred).

Juliana was sitting in her room considering her datebook, with her hands wrapped around a lukewarm cup of tea, when the softly simmering anxiety she'd had on the subject finally boiled over into action. With the holidays approaching and the wedding drawing near, she was busy for the foreseeable future. Even if he had written (he had not), even if he'd asked to talk to her (there was no suggestion that he would), where would she even find the time to meet him? Because of course she couldn't do it above-board; even though it had been years since the Watchword saga they were still individuals about whom there had been Talk, and it would have been unfair to Mr. Ainsworth for her to have done anything to encourage a resurgence of Talk so close to their wedding. So she wouldn't have been able to meet with him publicly, and the time that she had for covert meetings was quickly slipping away, and — and he had not asked to talk to her or even written her to confirm that he wouldn't care to talk to her. If he had written and said congratulations, or been angry, or anything — at least she would have known what he thought about the matter. He hadn't written, he hadn't asked, she didn't even know whether or not he had seen the notice, and that — the uncertainty of whether or not he would have written, more than anything else — was what drove her to abandon her cup of tea and fetch her coat.

Of course she still remembered the address.

She stepped into his living room, looking harried. She was at least still dressed from her day at the Ministry, but she'd let her hair down and put it in a long, loose braid over one shoulder. Her cheeks were pink from the cold — her father had been half-dozing over a book downstairs, and rather than walk through the room he was sitting in and risk questions she'd snuck out the front door of the house and then in again through the garden door to access the floo, and had not entirely dressed for the weather before she slipped outside. He was home, and of course she had anticipated that, but one wouldn't know it; her eyes were large and round with surprise, as though she had found herself here quite by accident. Juliana opened her mouth to begin the conversation and realized only after nothing came out that she had not considered what to say.

None of their notices had run alongside any ominous riddles about impending murders, which Juliana had decided to take as a positive omen. Not that she needed divination to reassure her. The engagement had been nothing if not smooth. She had met his parents and his sisters, all of whom were lovely to her and seemed agreeable in general. Mr. Ainsworth had been accommodating to her every request, not that she had many. She had no grand visions of her wedding; unlike some girls, she had not been dreaming about this from a young age. But even that seemed alright; her fiance seemed to understand that she had defined the purpose of her life without romance in mind, and did not expect her to love him. They talked frequently now that their relationship had changed, and she enjoyed their conversations and his company more generally. They were friends, and he did not demand more from her.

Since they'd begun posting the notices in the Prophet she had been on the receiving end of at least a dozen letters of congratulations — some superficial and sparse, from acquaintances that merely recognized her name and remembered her face and were polite enough to write — others lengthy and full of inquiries, from friends who knew her well enough to be surprised by this sudden development. Every notice brought a new batch of mail, but each month the wave was a little smaller than the previous month's, and they never contained the letter she was hoping for. Juliana hadn't admitted to herself that she was scanning each envelope for his handwriting, not at first — but after three months of small, steady disappointments she couldn't keep denying it. She wanted to know what he thought, even if it was nothing good. Was he angry? (Did he have any reason to be angry? They hadn't spoken since —) Maybe he never thought of her at all anymore. Maybe he hadn't even seen the notices in the paper, even though they'd been published three times in as many months. Maybe he didn't have the paper regularly delivered — that seemed plausibly like him, living up in Scotland detached from the rest of the world, avoiding — (was he avoiding the world, or just avoiding her? She didn't know which she would have preferred).

Juliana was sitting in her room considering her datebook, with her hands wrapped around a lukewarm cup of tea, when the softly simmering anxiety she'd had on the subject finally boiled over into action. With the holidays approaching and the wedding drawing near, she was busy for the foreseeable future. Even if he had written (he had not), even if he'd asked to talk to her (there was no suggestion that he would), where would she even find the time to meet him? Because of course she couldn't do it above-board; even though it had been years since the Watchword saga they were still individuals about whom there had been Talk, and it would have been unfair to Mr. Ainsworth for her to have done anything to encourage a resurgence of Talk so close to their wedding. So she wouldn't have been able to meet with him publicly, and the time that she had for covert meetings was quickly slipping away, and — and he had not asked to talk to her or even written her to confirm that he wouldn't care to talk to her. If he had written and said congratulations, or been angry, or anything — at least she would have known what he thought about the matter. He hadn't written, he hadn't asked, she didn't even know whether or not he had seen the notice, and that — the uncertainty of whether or not he would have written, more than anything else — was what drove her to abandon her cup of tea and fetch her coat.

Of course she still remembered the address.

She stepped into his living room, looking harried. She was at least still dressed from her day at the Ministry, but she'd let her hair down and put it in a long, loose braid over one shoulder. Her cheeks were pink from the cold — her father had been half-dozing over a book downstairs, and rather than walk through the room he was sitting in and risk questions she'd snuck out the front door of the house and then in again through the garden door to access the floo, and had not entirely dressed for the weather before she slipped outside. He was home, and of course she had anticipated that, but one wouldn't know it; her eyes were large and round with surprise, as though she had found herself here quite by accident. Juliana opened her mouth to begin the conversation and realized only after nothing came out that she had not considered what to say.

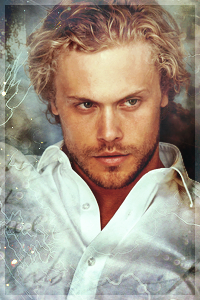

Prof. Marlowe Forfang

Jules